Handout

SPACs are currently all the rage in financial media.

Why? As with any investment being heavily promoted, you can almost always understand by simply looking at the incentives. SPACs are no exception.

What is a SPAC?

SPACs, previously called “blank check companies,” have been around since about 1980. The technical definition of SPAC is “special purpose acquisition company.” A SPAC is an alternative way for a company to go public. Most companies are private, meaning they are owned by a small group of people and do not have to share their financials with the world. However, as companies become larger, they often open their ownership to the masses by going public. Drawbacks to going public are increased regulation, a larger group of shareholders to answer to, and the requirement to produce your financial statements for the world to see. Companies go public to have easier access to cheap financing.

The traditional route of going public is through the IPO, or initial public offering process. At IPO, a company first offers its stock to the public and keeps the money from the proceeds to finance its operations. The IPO process usually takes about 18 months, drowns the management team in paperwork, comes with hefty fees paid to bankers, and brings in an unknown amount of financing. A SPAC is a little different.

How does a SPAC work?

A SPAC is a shell company that goes public via IPO at a discounted cost and expedited process. The only asset of the shell company is cash. The SPAC management team (ideally experienced managers) raises the cash in the shell company from investors. The cash will be used to complete an acquisition of a private company. The new combined publicly traded entity is the private company’s operations plus the SPACs’ cash, a much simpler and less expensive process for the private company to go public, and the private company knows they will receive exactly the amount of cash in the SPAC.

There are three stakeholders in a SPAC: the experienced management team that invests a small amount of money and creates the SPAC shell company, the private company being acquired, and the investors who provide the majority of the cash. The incentives are as follows: the management team receives outsized ownership of the company relative to the money they invest; the private company gets certainty in the amount of funding received and easier access to the public markets than via IPO (not to mention an experienced management team to bounce questions off); and the investors who provide the cash are hoping that the management team they are putting their cash with will be able to earn returns larger than the investors could earn themselves.

Who wins?

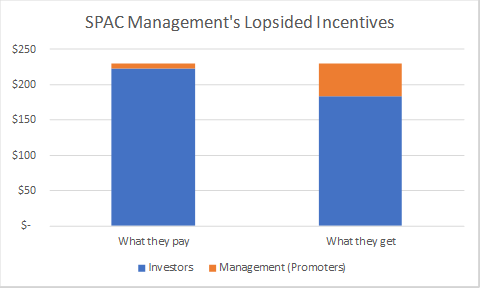

Currently, the incentive structure is positioned to massively favor the management team. If you notice who is promoting the SPACs on TV, it is usually the management team. How favored is management? Here is an example: A SPAC is being raised by a company a handful of my clients are invested in; we’ll call it Company A. The terms of the SPAC are that Company A puts in $6.6 million to receive 20% ownership of a $230 million SPAC—20% of $230 million is $46 million. Company A puts in $6.6 million to receive $46 million as long as Company A completes an acquisition. Even if the company acquired by Company A is a total loser and drops in value by $150 million its first day of trading, Company A’s 20% share of the remaining $80 million is worth $16 million. Company A gains about $10 million, while investors in the SPAC lose $150 million. In addition, if the SPAC performs well, Company A gets to purchase more shares at an advantaged price which lessens investor gains. This is a typical structure for a SPAC; easy to see why SPACs are all of the rage now—easy to promote SPACs if all you have to do to become wealthy as a SPAC manager is complete acquisitions even if they incinerate investor money!

Who loses?

As an investor in a SPAC, you are effectively paying Company A (or whichever management team founds your SPAC) a very high fee to pick a company to invest in for you. Historically, paying high fees for investments has not been a rewarding strategy. At Abacus Planning Group, we focus on low-cost investments, and we go to great measures to understand the incentives of all stakeholders before making an investment.

Incentives, more than opportunity, likely drive the SPAC popularity. It is not because a SPAC is going to magically offer amazing returns (unless you are a SPAC creator). The current structure incentivizes management to buy any company possible, good or bad.

While this article may sound critical, there is nothing obviously dubious about SPACs. If SPAC incentives become more balanced, SPACs could provide an effective alternative to the inefficient IPO process. However, as with any investment, earning outsized returns in SPACs is difficult and requires thorough research before anyone should consider an investment.

William R. Jeter

William R. Jeter